(Writing Talk is a type of short-for article centered around conversations about various aspects of writing/authorship. These aren’t usually long reads, but I think it’s fun to jot down some of my thoughts about the writing process as someone who loves the art of it all.)

You know, I almost have to give myself some credit with the restraint I’ve shown in creating these ‘Writing Talk‘ articles. Because, aside from my effusive love of fight/action scenes, there’s nothing I love more in storytelling than utilizing the technique of Chekov’s Gun…and yet, I’ve yet to do an article on that topic until now. I guess I better rectify that while I’ve got the chance here, and spend some time talking about one of my absolute favorite literary devices!

But, hold up…who is Chekov, and why should I care about his Gun? Good question, hypothetical reader, I’m glad you asked!

Chekov refers to Anton Chekov, an acclaimed Russian playwright, and the Gun in question is a theoretical gun that came up in discussions Chekov had about his philosophy of writing detail into stories. I’m going to quote someone making a reference to Chekov’s old works here, so it’s not Chekov’s technical words, but it encapsulates the spirit of his message. The man himself never directly said this, after all, only variations of this idea.

“Remove everything that has no relevance to the story. If you say in the first act that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third act it absolutely must go off. If it’s not going to be fired, it shouldn’t be hanging there.”

Sergius Shchukin (1911)

Do you get it? His idea here was that, as an author, you shouldn’t include a detail unless that detail is going to become important later in the story. If it won’t be important later, why have you wasted your reader’s time with a superfluous detail?

This conceit goes hand in hand with a different, but intrinsically similar, literary technique known as ‘The Law of Conservation of Detail‘, of which the general idea is that stories benefit from great detail being put into important plot/character elements, but suffer from extensive detail poured into unnecessary aspects. For example, if a character in a story calls someone on the phone, don’t bother describing the phone. All your readers know what a phone is. Only ascribe detail to parts of the story that actually matter.

Taken together, both of these literary devices essentially describe my own novel-writing style. I place heavy detail and emphasis on aspects of the story or characters that will actually become important to the narrative, while glossing over parts of the story that don’t matter much. I often don’t expend too much effort describing the layout of a room, for example, because instead I want readers to care about the conversation happening between the characters within said room. I don’t want to bog readers down with details that may distract them.

In fact, if one is going to pursue utilizing Chekov’s Gun within their writing, it practically becomes a necessity to make purposeful use of the Law of Conservation of Detail. After all, Chekov’s Gun is all about only addressing details when they will become important to the story later. If you’re throwing details everywhere all willy-nilly, your reader won’t know what is a Chekov’s Gun, and what is just some silly little thing you threw in there for whatever reason you may have had.

This might be confusing, so I’ll go over a few other examples of Chekov’s Guns in storytelling.

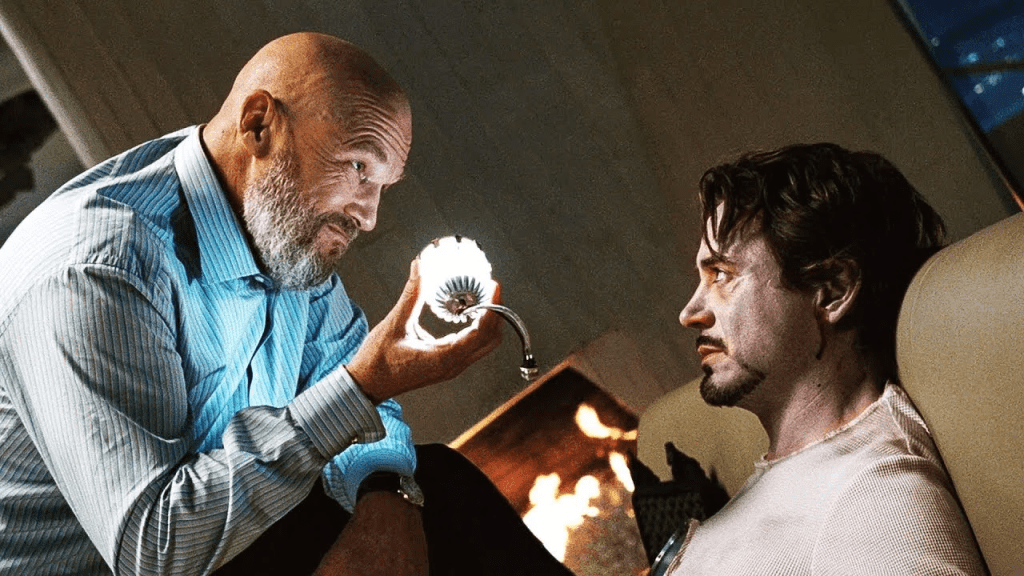

In the film Aliens, our main heroine uses a big power-loading machine for a rather menial task, but it demonstrates to the viewer that she knows how to operate this machinery. Guess what she ends up using to defeat the Xenomorph Queen at the end of the film? Or how about in the original Iron Man, where Tony Stark replaces an obsolete arc reactor with a stronger one, and Pepper keeps the old one in a little decorative case. When Tony’s stronger core gets stolen in the final act, guess where he manages to find a replacement from?

Chekov’s Guns also don’t really have to be physical objects either. I believe that the principle can be expanded to relate to anything the author introduces in a casual off-handed manner that ends up becoming vitally important later in the story. Like in Jurassic World where our main hero uses the raptor-taming technique demonstrated much earlier in the film to win the raptors back over to his side during the climax. Or the original Karate Kid, where Daniel’s trick he was practicing earlier ends up being what he uses to score the final point.

If you ask me, Chekov’s Guns are a two-fold literary technique. On the one hand they allow the reader to pick up on subtle clues that will have huge payoff later in the story. But on the other hand, I think they also help to cover the author’s butt, if you are aware of that phrase. By introducing in the early pages key elements of your story that you want to have a big final payoff near the end, you prep the reader for the eventual reveal without it having come across like some random happenstance that occurred with no setup or reason. A lot of anime tend to be guilty of the latter. Many big fights in anime will be solved by the protagonist whipping out some move that we’ve never seen before, and while it may have spectacle, it really lacks substance.

While Fairy Tail doesn’t completely avoid this trap, it’s pretty good at creatively circumventing it, and often with Chekov’s Guns. One of my favorite examples is Natsu’s big fight with Jellal early in the show, during the Tower of Heaven arc. Jellal willingly took a nasty hit earlier in the fight to try and one-up Natsu, and that ends up biting him in the butt badly when he fumbles in the home stretch due to the wound he suffered then catching up to him, allowing Natsu to land the finishing blow. It’s a wonderfully cathartic moment, and attentive viewers will have caught that initial Chekov’s Gun moment and be satisfied at the payoff, not scratching their heads wondering what the writers were thinking.

Now, as a literary technique, Chekov’s Gun is not without its criticism. Most critics of the technique argue that the reliance on Chekov’s Guns leads to stories becoming rote or predictable. One of the biggest critics is Ernest Hemmingway, the king of superfluous and meandering stories that are tedious to read (whoops, sorry, might’ve gotten a little heated there). There seems to be this belief that if an author likes to use Chekov’s Guns, that means that their story is barebones in terms of detail, and nothing more than predictable beats one after the other. Certainly, I could see how this worst-case-scenario sort of story wouldn’t be very enjoyable.

The thing is, a story that correctly utilizes Chekov’s Gun shouldn’t be like this. It’s not some sort of black-and-white, this-or-that kind of thing. Just because you like sprinkling in details that will become important later in your story doesn’t mean that your story has to be totally bereft of details. It doesn’t mean that you have to write a story that reads like “and then John saw a knife sitting on the counter, and knew for sure it would become very important, probably around chapter 30“. That’s ridiculous! Skillful application of the Chekov’s Gun technique should be practically invisible, but strong enough to plant the seeds of awareness in your reader’s mind, even if that aren’t consciously aware of it at the moment (that’s kinda the best case scenario, actually).

And another important counterpoint is that just because you know something is going to be important, doesn’t mean you know why or how. If an author introduces a Chekov’s Gun by mentioning that “Sarah even had an axe in her bedroom closet, hidden under her grandmother’s old coats“, obviously that axe will be important. But why or how? You have no idea! You can guess, but a truly talented author will surprise you! Maybe Sarah needs to cut through a door after she gets locked in her room, or maybe she has to fight off an attacker. Or maybe she is the attacker, and now your reader is twice as scared for the fate of the other characters, because you have the knowledge that Sarah has an axe, which they might not! Chekov’s Guns are supposed to be fun, not rote!

The point is, Chekov’s Guns are a lot of crucial and versatile than people seem to realize, and while not every story needs them, they can be really fun to include if you get the chance. I know I certainly love relying on them in my personal stories!

Keep on writing, friends!